Mid-air in C/229th!!!

©Daniel E Tyler, 1999

|

Around ANZAC Day, the Australian equivalent to Veteran's Day, my thoughts usually turn to my time in the service, even though those events are now more than half a lifetime ago. I've thought about that one year I spent in Vietnam so much over the last 28 years that sometimes I wonder how much of it really happened, and how much is the product of my thinking about it so much -- re-constructing events in my mind the way I wish they had been -- rather than the way they actually were.

But some things I am certain about. We had some good times and some GREAT flying. Most of the skills I've used as a pilot since then were developed and perfected flying those unfriendly skies.

A couple years ago, the release of "Black Hawk Board of Inquiry" findings into the mid-air collision between two Australian Army UH-60 helicopters near Townsville in June, 1996, brought back images of a not-so-great time.

In the Townsville accident, the Flight Leader was one of those who died. I was a Flight Leader in an Assault Helicopter Battalion for a few months -- way back then. I found out what it felt like to return to base without two of your helicopters and eight of your men -- including two of your best friends. I can still feel it . . . .

There is perhaps no other type of helicopter accident that is more certain to be fatal than a mid-air collision. The mere mention of the term "mid-air" will send a chill through any pilot. When I heard that word over the radio on the morning of 26th September, 1970, it cut through me like nothing else has since.

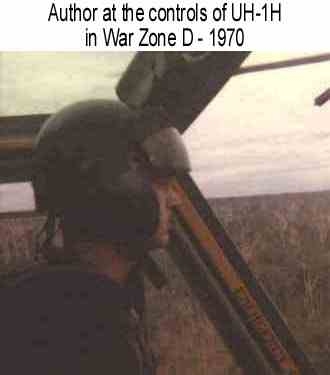

I flew UH-1H Iroquois for the US 1st

Cavalry Division (Airmobile) for twelve months from March, 1970.

The 1st Air Cav, as it was called, had pioneered the air mobility

concept in Vietnam only five years earlier. Bell UH-1's were the

backbone of the US Army's helicopter fleet. Any UH-1 was called a

"Huey" but there were several models around. The

"H"-model was the latest and most powerful

"slick" version at the time.

I flew UH-1H Iroquois for the US 1st

Cavalry Division (Airmobile) for twelve months from March, 1970.

The 1st Air Cav, as it was called, had pioneered the air mobility

concept in Vietnam only five years earlier. Bell UH-1's were the

backbone of the US Army's helicopter fleet. Any UH-1 was called a

"Huey" but there were several models around. The

"H"-model was the latest and most powerful

"slick" version at the time.

Troop transport and utility machines were called "slick's" while the attack helicopter version was called a "hog". By the time I got to 'Nam, most of the "hogs" were gone -- having been replaced by "snakes" -- the AH-1G "HueyCobra".

In the 1st Cav, aviation support was integral to the Division and was readily available to ground commanders down to Battalion level. There was the legendary 1/9th Air Cavalry Squadron -- whose pilots wore black Cavalry Hats. There was also Blue Max -- the aerial rocket artillery battalion that was part of DIVARTY; and the Dust-Off Helicopters from the 15th Medical Battalion. But most of the Division's Air Support came from the 11th Combat Aviation Group, consisting of two Assault Helicopter Battalions -- the 227th (of Chickenhawk fame) and the 229th -- and one Chinook Battalion -- the 228th.

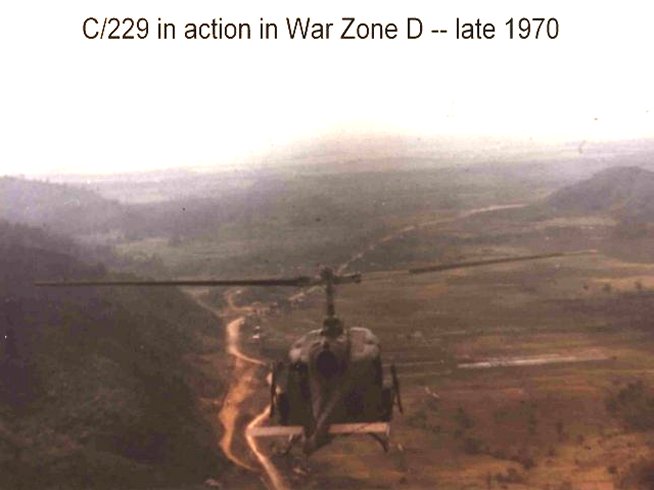

During most of 1970, the 229th AHB provided direct support to the 1st and 3rd Brigades of the 1st Air Cav. On 26thth September, my company, Charlie/229th (callsign North Flag), was tasked to supply a 'gaggle' of five slicks to support the 1/7th Battalion -- one of three rifle battalions in the 1st Brigade. We were to be escorted by two snakes from Delta /229th (call sign Smiling Tigers). 1/7th was operating out of Fire Support Base (FSB) Green in northern War Zone D, III Corps Region.

Things were fairly quiet in our Area of Operations (AO) at that time. We had seen a lot of action in War Zone C prior to the Cambodian Incursion, and the 11th Combat Aviation Group had spearheaded the assault into Cambodia. But for the three months after we pulled out of Cambodia, things had been pretty routine.

Most nights, off-duty pilots would write letters, drink beer, and listen to music in our hooch until we fell asleep. Overnight, the following day's tactics for airmobile assaults would be worked out by the various Brigade Staffs. By the early hours of the morning, tasks would be allocated to aviation companies.

The company operations staff would in turn allocate crews to aircraft and prepare a brief mission sheet for each aircraft commander (AC). Operations staff would then go around to the hooches and wake up the aircrew 45 minutes prior to first crank. We would drag ourselves out of our alcohol-induced stupor, stand in the cold shower until we could start to feel our bodies, and then dress and head for the mess hall -- picking up a copy of the mission sheet from the TOC (tactical operations center) along the way.

After shovelling down our gullets what the US Army officially described as "rations", "Peter-Pilots" (co-pilots) headed for the flight line to pre-flight while AC's returned to the TOC.

The mission sheets set out which crew members flew which aircraft and, if they were going out in the "RF" -- officially called the 'Reaction Force' but better known as the 'Rat-F..k' -- which position in the RF they would fly. The sheet also gave coded locations for PZ's (pick-up zones) and LZ's (landing zones) and the number of loads to be carried into or out of each location.

The RF normally consisted of six slicks -- divided up into Yellow and White Flights. Yellow-One was "Air Mission Commander" and flew Chalk-One position most of the time. Yellow-Two and -Three were Chalk-Two and -Three respectively; White-One, -Two, and -Three flew Chalk-Four, -Five and -Six respectively, in the formation.

White-One was second-in-command of the RF, and his flight could be detached -- for example if the LZ was too small to permit the entire RF to land at one time. The idea of having Yellow-One command the flight from the lead position was unique to the 1st Cav.

In most other units, the Air Mission Commander flew over-head in a "C&C" (command and control) ship -- often with the "Task Force Commander" on board.

Having checked for any last minute changes to the mission sheet from the TOC, AC's would then join the Peter-Pilots on the flight line. As they arrived, crew chief's and door gunners would be mounting the M-60's to the sides of the ships and routing the linked chains of ammo into the magazines.

It was customary in the 1st Cav for the RF to crank up thirty minutes prior to scheduled departure time and carry out a "commo check" on the three communications radios carried -- "Uniform" (UHF-AM), "Victor" (VHF-AM), and "Fox-Mike" (VHF-FM). That way, any maintenance or avionics problems could be rectified or a back-up ship brought on-line without delaying the RF's departure.

After the commo check the ships -- except for Yellow-One -- shut down and the crews returned to the mess hall for another cup of coffee and a smoke before launching the flight. Yellow-One would depart without shut-down and carry out reconnaissance of the proposed LZ's and PZ's before landing at the Battalion TOC to get more details on the tactical situation from the Task Force Commander.

On 26th September, 1970, I was the AC of Yellow-One and therefore the Air Mission Commander for the day. As usual, the eight pilots who shared our hooch had "partied" the night before.

One of our colleagues, Warrant Officer Bob Bauer, (personal call sign Little Ogre) had written a birthday card to his grandmother and asked us all to add our greetings. We'd listened to music supplied by Warrant Officer Mark Holtom (personal call sign Hokus Pokus) and had a few beers. As usual, at about 0230 hrs, we had all joined in singing along to Country Joe and the Fish's performance of "'I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die' Rag" from the Woodstock album.

Only about three hours later we were still joking about the birthday card as we rode down to the mess hall in the back of a 3/4 ton truck. The joking continued even through breakfast. Warrant Officer Steve Adams (personal call sign Redbush) couldn't leave it alone. Captain Bob Barnaba finally put an end to the frivolity.

As we ate breakfast I scanned the mission sheet and saw that Little Ogre was AC of Yellow-Two and Hokus Pokus was at White-One. I was pleased to have two experienced and dependable AC's in those key positions. And because they were key positions, operations had also assigned good Peter-Pilots to fly with them. First Lieutenant Francis Sullivan (Sully) was with Holtom; First Lieutenant Warren Lawson (Wild Bill) was with Little Ogre. Both of the Peter-Pilots showed good potential and were expected to make aircraft commander shortly, themselves.

Redbush had a "New Guy" Peter-Pilot with him in Yellow-Three and Bob Barnaba (our unit Instructor Pilot) had another "New Guy" Peter-Pilot at White-Two, which was "tail-end Charlie". The mission sheet only called for a five-ship 'gaggle' that day so there was no White-Three.

Larry Wall was my Peter-Pilot in Yellow-One. He'd been an AC but had been downgraded for letting an FNG (F..king New Guy) flare too steeply and knock the tail rotor off on an approach. Larry had been a flight school class-mate of Little Ogre and Hokus and the three of them had ridden the same plane to Vietnam five months earlier. You don't get much tighter than that.

Larry was a damn good driver who'd had more than his share of bad luck. He was always welcome as my Peter-Pilot.

After

we finished the commo check, I told Little Ogre to bring

the flight out in thirty minutes, to rendezvous with the Smiling

Tigers en route, and to meet me just south of FSB Green.

I then departed Bien Hoa Army Heliport and headed north across

the sleepy little village of Tan Yuen and across the Dong Ngai

River.

After

we finished the commo check, I told Little Ogre to bring

the flight out in thirty minutes, to rendezvous with the Smiling

Tigers en route, and to meet me just south of FSB Green.

I then departed Bien Hoa Army Heliport and headed north across

the sleepy little village of Tan Yuen and across the Dong Ngai

River.

Larry Wall called Bien Hoa and then Phuoc Vinh Artillery Control -- ascertaining whether any artillery or mortar fire might impinge our proposed flight path. I notified our departure to Company, Battalion, and Brigade Ops in turn.

As we neared Phuoc Vinh, a bank of cloud starting at about 500' above ground-level (AGL) and rising up to about 4,500', extended as far to the east and west as I could see.

We climbed to 5000' and continued over the top -- re-setting the altimeter to 29.92 inches and carrying out our "DER Check" (Daily Engine Record Check -- nowadays referred to as "Trend Analysis").

About 15 miles south of FSB Green the cloud layer broke up and Green was virtually in the clear. I radioed back to Company Ops to get a message to Little Ogre that he could bring the flight out over-the-top at 5000' -- and that there would be no problems getting down at Green. I also made contact with the Battalion Commander of 1/7th -- Lieutenant Colonel "Mad Anthony" Labrozzi.

"Mad Anthony" was a controversial guy who seemed to be more interested in winning encounters with the bad guys than he was in playing Army politics. I thought he was a great commander and I liked him personally -- but then we were probably both out of step with reality.

I radioed ahead that I would check out the proposed LZ's and PZ's and then come in to land at his TOC. I needn't have worried about the LZ's and PZ's. Labrozzi's Operations Officer -- a Major whose name I just cannot remember -- was an aviator who had formerly commanded a Cobra company in the 227th. The LZ's and PZ's he and Labrozzi had chosen were all adequate "five-ship'ers".

I noted the long axes, shapes, obstacles, and land-marks at each site -- and the likely hiding places for any bad guys -- mentally constructing flight paths into and out of each one so as to avoid the G-T (gun-target) lines and give the Cobras the best chance at suppressing possible hostile locations without exposing themselves too much.

By the time I landed at FSB Green I had a fairly well-developed plan for running the mission -- subject to what Labrozzi and his S-3 had to tell me about friendly -- and possibly enemy -- troop locations. I asked Larry Wall to shut down but stay with our ship and monitor company VHF -- just in case the Cobra gun ships called in early.

As I walked through the perimeter defences and into the TOC -- Colonel Labrozzi rushed out to meet me, saying that Yellow-Three was trying to contact me urgently on the Battalion net.

I raced into the TOC just in time to hear Redbush on Fox-Mike saying there had been a "mid-air" within the flight, both aircraft had fallen out of sight into the cloud layer, and there were two columns of smoke coming up through the cloud.

He said he thought they were just east of FSB GarryOwen -- an abandoned Firebase at a spot the Vietnamese called Rang Rang -- but he couldn't tell exactly because of the cloud.

A "mid-air"!! . . To this day I find it strange that such a simple little expression -- just two syllables made up of six letters and a hyphen -- can slam into a helicopter pilot's gut with such impact.

I asked Redbush who was involved. He said Yellow-Two and White-One had meshed rotors while at 5000' over-the-top.

I knew, as I ran past Colonel Labrozzi, across the firebase to the perimeter where the Huey was parked, that Little Ogre and Hokus were dead. Son-of-a-bitch!!! Not Little Ogre and Hokus -- not both at the same time!!! God-damn!!! We'd just written silly messages on a birthday card to Little Ogre's grandma not six hours before!! Hokus' Carlos Montoya Classic Guitar tape was lying on my bunk back at Bien Hoa. The greasy bacon and eggs we'd all shared at breakfast only an hour before still tossed around undigested in my stomach as I ran.

As I crossed the berm at the edge of the firebase I spun my arm around over my head, signalling Larry Wall to crank up. He had the rotors spinning by the time I hit the saddle and started to strap in. I yelled that there had been a mid-air but he had just taken the same message over "Victor".

For a couple seconds after we blasted off low-level to the south beneath the overcast, I was so absorbed in asking myself why and how it could have happened that I forgot about Larry. Then I looked over and saw him -- staring straight ahead -- his eyes open but his face totally devoid of any expression.

Although I thought of them as brothers, I'd known Little Ogre and Hokus for just five months. Larry had been pals with them for eighteen months. I decided to have him fly while I checked the mission sheet to remind myself who else was on board.

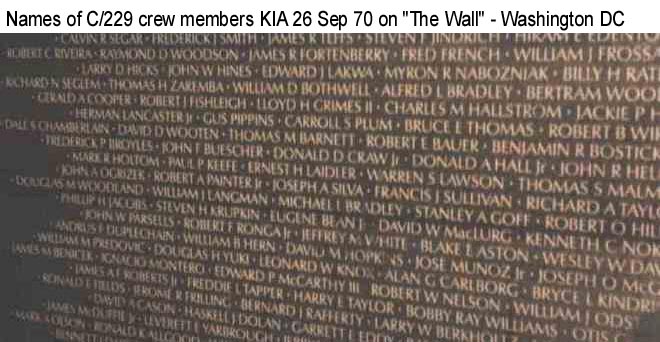

Woodland (Crew Chief) and Painter (Door Gunner) were with Wild Bill Lawson and Little Ogre in 68-16123 -- Thumpy 1. Hall and Laidler were with Sully and Hokus in 68-15648 -- Cherry Buster.

All those guys were experienced. Woodland and Hall were two of our best crew chiefs and they were in two of the strongest "H"-models we had in the company. "What the hell could have happened?" I asked myself.

I found myself wondering what formation they had used en route. With Yellow-One gone ahead of the rest of the flight, there was only a four-ship formation with Little Ogre moving up to Chalk-One and Hokus in Chalk-Three. How could they have collided?

All of those thoughts had taken about ten seconds to think. Until we found both aircraft and accounted for all crew, we had to consider this a search and rescue mission. I had to believe they had managed to regain control before impact. The reports of two columns of smoke coming through the cloud layer made it hard to believe that, but I called Yellow-Three (now leading a two-ship flight) anyway and checked again on the location.

Redbush said he couldn't see anything on the ground but, based on the time intervals, he thought they were just east of Rang Rang. I figured that Little Ogre would have maintained a direct track from Bien Hoa to FSB Green so the reciprocal heading from Green seemed the most logical choice. It was only about nine or ten minutes flying time.

There was a mist below the over-cast but I could still see the two columns of black smoke extending from the triple-canopy jungle up into the 500' ceiling from several "clicks" (kilometres) away. Each column looked sort of like the funnel-cloud from a tornado.

Bob Barnaba in White-Two had found a hole in the overcast and had spiralled down through it and was approaching from the opposite direction. The escort gun ships had arrived and were circling over the top with Yellow-Three. I sent them all to FSB GarryOwen to shut-down and wait.

I checked with Company Ops on FM and found they had already been informed. They had already requested a Dust-Off from the 15th Medical Battalion and Blues from the 1/9th Air Cavalry to attend.

Medevac (Dust-Off) helicopters were normally hoist-equipped. The Blues were a rifle platoon carried on board a flight of UH-1H's and were used for ground reconnaissance. They normally carried rappelling ropes and were trained to use them. They were available on short notice and were often used to secure air crash sites in the jungle until an LZ could be cut and conventional troops inserted. The Blues sometimes even carried their own chainsaws with them.

With support on the way, we arrived at the column of black smoke located furthest to the north and looked down at an inferno. I took the controls back from Larry and hovered just at the tops of the trees. The fuselage was on its starboard side and was totally engulfed. Unlike the civilian helicopters made from aluminum-alloy -- most military helicopters were made of magnesium and burned at around 4000oF.

We circled around the tree tops just above the tiny hole the Huey had made and Larry stared but still didn't say anything.

There was no sign of anyone around the outside of the aircraft and though we couldn't see through the flames we knew they were all inside and that they were dead. I guess we all hoped that no-one had survived the impact.

The other crash site was about 180 metres to the south west. It looked exactly the same except that we couldn't see the main rotor blades anywhere. There were a couple spots within 60-70 metres where there was a gap in the top canopy. I got my door gunners to guide me down into two or three different spots but we could only get to about 60 feet above the ground and then we couldn't go any lower.

I flew back to the first crash site and tried to find a way to get down, but once again we couldn't get anywhere near low enough to put anybody out. I think at one stage we must have just circled for about ten minutes -- nobody saying anything -- just watching the helicopters burn away to nothing. During this time I started to emerge from the shock and to think again.

It dawned on me that if I didn't stop screwing around the company would be down three crews instead of two -- and that my parents would be getting a visit from an Army officer just like the others' would be sometime over the next few hours.

As soon as the Blues arrived I gave their flight leader a quick "sit-rep" over the radio and then flew to FSB GarryOwen. I never returned to the crash site again, even though I flew in that same area for several more months before going home.

En route to GarryOwen I radioed the CO of the 1/7th Battalion and told him I would be getting replacement helicopters as soon as I could and we would still try to fly his missions for him. I also radioed back to Bien Hoa and was told that the XO was on his way out in the CO's ship -- the CO was on R&R at the time. Two other ships were being readied for departure and would join me at GarryOwen within the hour.

I approached to a position at the front of the lead "Huey" parked along the abandoned runway at GarryOwen. As we shut down I could see the crews gathered around the trail ship. I left Larry to shut down and walked over to talk to Adams and Barnaba.

They told me that the flight was level at 5000' over the top in a "diamond" formation. Little Ogre had called for the flight to loosen up and for everyone to make their DER checks. This entailed setting the altimeter to 29.92 inches of mercury and pulling a steady 40 pounds of torque at 6600 N2 RPM, then recording the EGT, N1, airspeed and oil temperatures and pressures.

We usually took the readings while flying to the nearest 1000 feet and because of minor differences in altimeter calibration and also because different ships flew at slightly different airspeeds at 40 pounds of torque, it was necessary to loosen up the formation while the DER checks were done. Usually the Peter-Pilot flew and kept a look-out, the AC read the instruments and recorded the results, and the gunner and crew chief kept a lookout from their positions.

Little Ogre had held course while Hokus diverged from his port echelon position; Redbush diverged to starboard from his echelon position; and Bob Barnaba had dropped well back.

Nothing was said over the radio and nobody knows why, but Redbush looked up from writing down the DER check just in time to see White-One converging onto Yellow-Two.

Redbush said that Yellow-Two's main rotor on the retreating side cut into the cockpit of White-One and then separated entirely. The aircraft rolled right and disappeared into the cloud layer. White-One entered the cloud out of control in a steep dive.

Redbush said that he thought he had seen one body falling clear of either aircraft before they entered the cloud but amongst all the flying debris from the collision he couldn't say who it was or which aircraft it fell from. We were to learn later that one man had been decapitated in the collision and that one body had been found a short distance away from what was left of a helicopter.

By the time Redbush and Bob Barnaba had filled me in on what happened, my crew had finished tying down our machine and had joined the group. The XO (acting CO) had arrived and shut down.

I decided I needed to say something to what was left of my flight. It seemed like everyone there wanted someone to say something. I just couldn't think of what to say. But I was "Yellow One" and it was my job to try.

I've heard since about a phenomenon known as the "dissociation reaction" which manifests itself in life threatening or extremely stressful situations, where a person involved remembers things as if they were a third party. I know that happens, because I remember talking to the flight crews that morning as if I had been a spectator standing off to the side.

I remember seeing this guy wearing my name tag, standing in front of the group of guys sitting on the ground or leaning against one of the Hueys. I remember that the guy was speaking in a clear and authoritative voice, telling the troops to forget about what had just happened and concentrate on getting on with the job . . . telling them that we still had missions to fly. I remember thinking how strange it sounded to speak so clearly when I felt as shaky as s...t inside.

I remember one of the gunners who had witnessed the mid-air was crying and just couldn't get it together. I asked the XO to give me his door gunner for the rest of the day and to take the kid who was crying back to Bien Hoa with him. I remember being surprised that I sounded so much like a "lifer" -- like I was "regular Army" -- not on a short-term commission.

After a little while the two replacement machines arrived with their crews. I re-arranged the slots in the flight so that Redbush was Yellow-Two and Bob Barnaba was at White-One. We then cranked up and headed up to Green to fly Colonel Labrozzi's missions for him. I remember that Labrozzi was very low-key and sympathetic when we arrived -- which seemed so out-of-character for him. I guess that was the sign of the true commander that he really was.

For

some reason, as clear as my memory of the first few hours of that

day are all these years later, my memories of the rest of the day

are extremely hazy and confusing. I don't recall that Larry spoke

at all for the rest of the day.

For

some reason, as clear as my memory of the first few hours of that

day are all these years later, my memories of the rest of the day

are extremely hazy and confusing. I don't recall that Larry spoke

at all for the rest of the day.

What bothers me is that I have images of that day in my mind which I cannot explain. I recall being told that some abandoned hooches had been found at the edge of a clearing which were probably NVA and that we should destroy them. I have a recurring image in my mind of hovering up next to each of the hooches in turn, hooking the toe of the skid under the roof and lifting on the collective while one of the gunners climbed down the skid with an incendiary grenade which he tossed through the crack I had created; then quickly backing off as each hooch erupted in flames in front of us.

Those images are so clear and so consistent that I'm sure that it must have happened. The only thing is, I have no idea why we would have ever done it that way when we had Cobra gun ships working with us. But I guess it doesn't matter now.

When we got back to Bien Hoa that night Phil Seefeld (personal callsign Hometown Hero), who had been my room-mate in college before we both joined the Army and went through flight school together, met me at the flight line. We had both made solemn promises to each other's parents before we left for Vietnam that we would look after their son over there and make sure he got home safely. Phil shared the same hooch with Little Ogre, Hokus, Larry Wall, Redbush, myself and a couple others. He had been rostered off that day.

When the news had first been radioed back to company ops, it had been reported that the lead ship was one of those that crashed. Phil had assumed that was me, since I was the Flight Leader. He had gone for a three-hour walk, trying to figure out what he was going to say to my parents. It was only after he came back that he found out it was Yellow-Two and White-One - not Yellow-One - that had been involved.

But Phil still lost two room-mates that day. He came out to the flight line because he wanted to tell me how p....ed off he was (at me) that he had to go through those couple of hours thinking I'd been killed and how he'd have to go home and face my family. There was nothing I could think of to say.

The next day I was told that a memorial service would be held in the battalion chapel on 1 October. I had been appointed to eulogize the officers. One of the platoon sergeants had been appointed to eulogize the enlisted crew. I remember thinking, "Isn't that just like the Army. Even after they're dead the officers can't fraternize with the troops." But I guess it had to be that way.

I think I would rather have flown into a "hot LZ" than to stand up in front of the company and most of the battalion staff and talk about Little Ogre, Hokus, Wild Bill and Sully. The expression "only the good die young" sure applied that time. They were amongst the best we had. In the end I think I must have done okay - 'cause even the battalion commander had tears in his eyes when I finished.

I've often thought since then that a pilot does not truly come of age as an aviator until he or she can attend a memorial service where the helmets and boots of fallen comrades are neatly lined up at the front of the chapel, and then get back in the saddle to fly the next day. But I attended too many memorial services in 1970.

That's why I had such a hard time watching

the TV coverage of the service for the Townsville Black Hawk

victims -- something about the bayonets stuck into the ground

with the berets over the rifle butts hit awfully close to home

for me.

That's why I had such a hard time watching

the TV coverage of the service for the Townsville Black Hawk

victims -- something about the bayonets stuck into the ground

with the berets over the rifle butts hit awfully close to home

for me.

I didn't have to talk about Woodland, Painter, Hall and Laidler at the memorial service -- but I've got to say that they were damn good men. I knew Hall the best. His parents named him Donald but the Army made him a cook in Vietnam and cooks in the Army tend to get nicknamed Spoon.

The flight crews used to give the non-flying members of the company a pretty hard time. "R.E.M.F." (rear echelon m...er-f...er) was hardly a term of endearment among flight crews. Spoon Hall hated that and he hated his nick-name. So he volunteered to be a door-gunner.

It took awhile before the First Sergeant let him make the change -- after all, good cooks contributed a lot more to the war effort than good door gunners -- but "Top" finally relented.

On his very first day as a gunner, Spoon was in the same crew in which I was the Peter-Pilot. We got called to a night emergency re-supply mission up in the "Fishhook" of Cambodia and got the s..t shot out of us. Spoon got a Purple Heart and I got a DFC. Although he had proved to everyone that he was definitely made of the "right stuff", he still couldn't get rid of the nickname Spoon.

I've often wondered whether his parents knew they lost their son because he didn't like his nickname. But whatever anybody called him, he was a good guy, a damn good gunner, and he went on to become a good crew chief.

The loss of two Hueys and eight men on that day was certainly a blow to C/229th. We had lost six in a single-ship accident about three months before. Other losses were one and two men at a time.

About two third's of my company's losses during my tour in Vietnam were not directly related to combat activity -- they were due to aircraft accidents. Tactical flying techniques have more inherent risk than conventional flying techniques -- but are designed to reduce combat losses.

I believe that we often failed to pay sufficient attention to basic aviation safety because we focussed too much on the enemy threat. In the end, crashes killed twice as many as the enemy killed.

I assume that there was some formal

investigation and report into the accident of 26 September, 1970.

I assume that there was some formal

investigation and report into the accident of 26 September, 1970.

But I honestly do not remember being interviewed or taking part in any inquiry. Nor do I recall reading any official findings as to the cause of the mid-air collision.

I have a pretty good idea what happened. Though we had not had that much enemy activity since we pulled out of Cambodia three months before, we were flying a lot of hours and most pilots were at or in excess of their 110 hour per month nominal limit. Sometimes my own 30-day total was up around the 160-hour mark. It was accepted practice for the battalion flight surgeon to issue waivers. We were fighting a war, after all.

But that wasn't the main thing. I've thought about it a lot, and I think it had a lot more to do with the particular combination of crew members in particular slots at that particular time that allowed the collision to happen.

Both AC's were very experienced and very professional. They would have almost certainly done the close flying during the combat assault missions themselves. Equally, they would have given their Peter-Pilots as much stick time as they could during phases of flight that were perceived to be less critical -- such as the transit from base to AO. They would have felt comfortable with their eyes inside the cockpit, taking the DER check readings, knowing that at least three other sets of eyes in each aircraft were supposed to be keeping a look-out.

Both Peter-Pilots were particularly conscientious. They would have almost certainly been watching the respective AC's closely -- knowing that they would soon be in that seat -- making sure they knew what was expected of them.

No doubt they knew they were supposed to maintain a look-out during the DER checks, but the formation had been loosened up and the urge to watch how the AC did that particular task would have been great.

Even if the Peter-Pilot in Chalk-One was looking out, he would never have seen Chalk-Three approaching from echelon left. In the Cav, Peter-Pilots flew in the command (right) seat and AC's flew in the co-pilot (left) seat which had better visibility due to the off-set instrument panel.

The crew chief's, too, were conscientious. They were the sort of crew chief's who were likely to be interested in how their aircraft was performing and they would have been anxious to monitor the conduct of the DER check. Anyway, the crew chief on the trail aircraft would not have been able to see it's convergence onto the lead.

The gunners were newer to aviation than the rest. Flying would have still been exciting and interesting, though they had probably been in the job just long enough to feel comfortable with what they were doing and to start to feel curious about what was happening up front with the "DER-check" that they had heard about over the intercom. The gunner in the lead ship was on the blind side, and it would have been necessary for the gunner on the trail ship to divert his eyes inside for only a few seconds to allow the accident to occur.

No one can know for sure exactly what happened, but I think something like I've described would be a fair start at a reconstruction. I doubt if, after all these years, it matters to the families exactly why they lost their loved ones.

But it matters to those of us who still fly if there are lessons to be learned -- lessons that might prevent a similar accident happening again. If you know something of the pain suffered by those who are left behind in an air crash, you can better appreciate how important it is to pay attention to the small details in aviation.

Larry Wall was closest of anybody in C/229th to both Mark Holtom and Bob Bauer. All three had met the others' parents and families at their Flight School graduation.

The Bauer's, not knowing then that Mark Holtom had also died in the same mishap, requested either Mark or Larry as escort for Bob's remains.

Mark's family, also not knowing that Bob had been killed, requested either him or Larry to escort Mark's remains. The Bauer's lived on the east coast and Holtom's family lived on the west coast -- as did Larry's family.

It was understandable that Larry would choose to escort Hokus back home while the remains of the other seven were accompanied by servicemen detailed to that job but who did not know them.

Larry Wall was able to tell Mark's family what had happened first hand. I finally worked up the courage to write to the Bauer's a couple months after the mid-air. I then went to visit them in New York shortly after getting back to the world.

They told me that the birthday card we had all signed for Little Ogre's grandma had arrived on 29 September, 1970 -- on her 86th birthday -- and had brought them all much joy. Then, three hours after the mail delivery, an Army officer from West Point arrived with the heartbreaking news. I was surprised that it took so long to notify them, but I guess identification of the remains was extremely difficult, given the ferocity of the post-crash fire.

I've never had any contact with any of the other seven families but I stayed in contact with the Bauer's by letters and Christmas cards over the years. They learned to laugh again, but it was never the same. I visited them in 1984, after they had retired to Florida.

In one corner of

their lounge room was Bob's flight school graduation photo

alongside his medals mounted and encased.(see photo at left)

There was also the US flag which had draped his coffin at the military

funeral --neatly folded into a triangular shape and encased to match the

medals.

In one corner of

their lounge room was Bob's flight school graduation photo

alongside his medals mounted and encased.(see photo at left)

There was also the US flag which had draped his coffin at the military

funeral --neatly folded into a triangular shape and encased to match the

medals.

The private shrine also included a collage of snapshots from Vietnam. I stared at the captions beneath the photos -- as well as Little Ogre there was Larry, Hokus Pokus, Redbush, Hometown Hero, Gook Body, Scruggs -- even one of me -- Gentleman Dan -- all residents of The Ogre's House, as we had named our hooch. I couldn't believe how young we all looked.

Mr Bauer died a couple years later; and Mrs Bauer passed away in '96. In her last years, suffering badly from Alzheimer's Disease and in a nursing home, she sometimes wondered aloud where Bobby was, and why he didn't come to see her. Every time she was reminded that Bobby had died in Vietnam, it broke her heart all over again.

I guess that sort of thing has happened with the families of the Black Hawk accident victims, and will undoubtedly go on for decades.

Is there a point to it all? Are there any lessons to be learned from something that happened so long ago? Or was all the pain and sorrow for nothing? Hell, I don't know.

I certainly learned a few things. I learned that it is not fun to watch your hooch-mates burn; or to stand beside their boots and helmets at the front of the chapel and try to eulogize them; or to visit their parents to try to explain what happened.

But I learned some other stuff, too -- stuff that has helped me stay alive long enough to be regarded as a relic in the eyes of some of the young pilots coming into the EMS industry.

I learned that no matter how much of a "hot stick" you might think you are when you're young and at your physical peak -- no matter how strong and dedicated and serious you think you are -- no pilot is ever as good a judge of his own fitness and fatigue levels as the calendar and the clock.

I've learned that those of us who think we are so good that we can afford to get on the booze for half the night in the belief that a large dose of caffeine and a small shot of adrenaline will fix us up in a few hours -- are only kidding ourselves. We are also gravely endangering our innocent passengers and crew -- but we don't like to admit that.

I've learned that there is no such thing as a "milk run" in a helicopter. And even though we all tell our customers and the regulators and the media how safe helicopters are -- we ought not begin to believe our own publicity. Helicopters nowadays are pretty safe. But some of the twits flying them can be bloody dangerous!!!

One of the saddest things I've learned is that there is something about human nature that makes us believe we are bullet-proof -- especially when we are young. Accidents always happen to other people -- people whose faces we don't recognise and whose families we don't have to comfort. And of course we would never do anything that stupid.

But we do. We do stupid things all the time and then we confuse the fact that we got away with it, with being safe. I can tell you from experience that all those delusions about being bullet-proof and being a "hot stick" -- they all melt away rapidly in the presence of burning jet fuel.

I can tell you that when you watch someone burn -- someone who you know in your heart (even if your ego would never admit it) was a better pilot than you are in your very best dream -- it will cure you of those delusions -- if only for a little while.

I am not suggesting that those same lessons learned the hard way in Vietnam were ignored in the case of the Townsville Black Hawk crash. That tragedy brought its own lessons - I understand the Board of Inquiry Report contained seventeen volumes and identified sixteen directly-causative factors and twenty-six contributory factors.

I doubt whether it's any solace to anyone, but at least that Black Hawk accident happened in a critical phase of a high-risk operation -- during a maneuver when you might expect such an accident to occur (if you know anything about night helicopter assaults) -- not in a routine transit flight.

But, on a simplistic level, if all rotary-wing aviators paid close attention to the tiny details; if we all disciplined ourselves to keep our guard up every second, when we are flying; if we concentrated on doing our job exactly right and demanding that all other members of the crew do their jobs exactly right -- maybe we wouldn't have to attend or watch those painful memorial services as often.

It seems such a shame we have to go through that periodically to learn those lessons.

DET

Daniel E Tyler

C/229 70-71

heli-con@acay.com.au

John Hubbs

229th's-Webmaster

skytrooper@stic.net